You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

Best to never play Test cricket | Draft Part 2 underway...

- Thread starter VC the slogger

- Start date

- Joined

- Jun 8, 2014

- Location

- Pune

- Online Cricket Games Owned

- Don Bradman Cricket 14 - PS3

- Don Bradman Cricket 14 - Steam PC

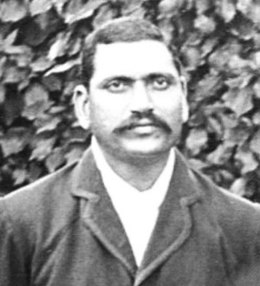

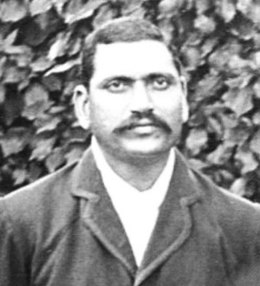

My first pick would be Palwankar Baloo, who can be regarded as one of the best left-arm spinners produced in India. He bowled left-arm orthodox spin with great accuracy and the ability to turn the ball both ways. He was also a moderately skilled lower-order batsman. He was the first member of the Dalit (also known as the "Untouchable") caste to make a significant impact on the sport. Although being one of the finest cricketers of his time, he was never allowed to lead the team as a captain because of his so-called lower caste. He just played 33 first-class matches and took 179 wickets with the bowling average of 15.21. After his cricket career, he went into politics and lost in Municipality elections against Dr. Ambedkar in 1937.

Asham's XI1)

2)

3)

4)

5)

6)

7)

8)

9)

10)

11)

@ahmedleo414 to pick next

Last edited:

My first pick would be Palwankar Baloo, who can be regarded as one of the best left-arm spinners produced in India. He bowled left-arm orthodox spin with great accuracy and the ability to turn the ball both ways. He was also a moderately skilled lower-order batsman. He was the first member of the Dalit (also known as the "Untouchable") caste to make a significant impact on the sport. Although being one of the finest cricketers of his time, he was never allowed to lead the team as a captain because of his so-called lower caste. He just played 33 first-class matches and took 179 wickets with the bowling average of 15.21. After his cricket career, he went into politics and lost in Municipality elections against Dr. Ambedkar in 1937.

Asham's XI

1)

2)

3)

4)

5)

6)

7)

8)

9)

10)

11)

Palwankar Baloo

@ahmedleo414 to pick next

That’s a frankly amazing pick! Hats off..

He was also a pretty decent lower-order batsman if you ask me, and can be classed as a bowling all-rounder.

James Aitchison

It's 5 am here right now so I'll do the write up later.

But here are his stats

First class

Matches 50

Runs scored 2,786

Batting average 32.77

100s/50s 5/13

Top score 190*

Balls bowled 18

Wickets 0

Bowling average –

5 wickets in innings –

10 wickets in match –

Best bowling –

Catches/stumpings 22/–

@Aislabie you have the next two picks

It's 5 am here right now so I'll do the write up later.

But here are his stats

First class

Matches 50

Runs scored 2,786

Batting average 32.77

100s/50s 5/13

Top score 190*

Balls bowled 18

Wickets 0

Bowling average –

5 wickets in innings –

10 wickets in match –

Best bowling –

Catches/stumpings 22/–

@Aislabie you have the next two picks

Here is a little bio i got from James Aitchison from Cricket Scotland's Hall of Fame page

"

James Aitchison was born in Kilmarnock and made his first class debut in 1946. Along with John Kerr, he holds the record of being the only Scottish player to score a century against full test-playing sides.

Only two other players have appeared more times in first class cricket for Scotland, and he holds the team’s record for most career runs and highest individual score. In the match against Ireland in 1959 he batted throughout the first day to make 190 not out.

At the time of his retirement, Aitchison had notched up the highest number of international caps for Scotland-69 and also easily the highest run aggregate in such matches 3,699.

Aitchison is best remembered for the unique feat of making two centuries against the touring teams; but five other centuries in his 69 capped internationals, and 30,318 runs in all matches make up an impressive tally.

In club cricket for Kilmarnock he made 18,344 runs with 56 centuries.

He served as a minister in the Church of Scotland for 34 years until his retirement in 1986.

"

"

James Aitchison was born in Kilmarnock and made his first class debut in 1946. Along with John Kerr, he holds the record of being the only Scottish player to score a century against full test-playing sides.

Only two other players have appeared more times in first class cricket for Scotland, and he holds the team’s record for most career runs and highest individual score. In the match against Ireland in 1959 he batted throughout the first day to make 190 not out.

At the time of his retirement, Aitchison had notched up the highest number of international caps for Scotland-69 and also easily the highest run aggregate in such matches 3,699.

Aitchison is best remembered for the unique feat of making two centuries against the touring teams; but five other centuries in his 69 capped internationals, and 30,318 runs in all matches make up an impressive tally.

In club cricket for Kilmarnock he made 18,344 runs with 56 centuries.

He served as a minister in the Church of Scotland for 34 years until his retirement in 1986.

"

@Aislabie its been more than 24 hours since my last pick... I have the next pick, should i pick again?

Technically he has a double pick i.e the next person to pick after 24 hrs is also him, so I reckon the ball’s still in his court..

Aislabie

Test Cricket is Best Cricket

Moderator

Ireland

PlanetCricket Award Winner

Champions League Winner

Okay, so first of all apologies for my lateness - I didn't pick up the tag to make my pick.

So my first pick will be a man I've written an extensive profile on in the past:

Albert Moss

Albert Moss

First-class stats: 26 wickets @ 10.96 (2 5WI, best 10/28) in 4 matches

Few have heard of former Canterbury fast bowler Albert Edward Moss, and given that he played all of four first-class matches there would usually be very little reason for them to have done. Born in Coalville, Leicestershire in 1863, he made the difficult decision to emigrate as a young man to escape the spread of tuberculosis through his family. It meant leaving behind his fiancée, Mary Hall, with the aim that they would be reunited in New Zealand.

He settled in Canterbury, New Zealand; where cricket had been a recreational activity for him in England, it increasingly became a way of life as he crafted a fearsome reputation for himself as a fast bowler at club level for Lancaster Park. His numbers spoke for themselves and demanded his selection for a first-class debut against Wellington at Hagley Oval in 1889. Batting at number eleven, his debut began inauspiciously as he was out for a duck, caught by Henry Lawson to become Charles Dryden's seventh wicket in the innings.

The debutant was entrusted with the new ball, and would be running in with the full weight of his reputation thundering behind him. With only three runs on the board, he struck: Wellington captain William Salmon out, caught behind by wicketkeeper George Marshall. Moments later, the dangerous Robert Blacklock was out too, caught by Charles Garrard. Malcolm Moorhouse became Moss' third wicket and Marshall's second dismissal before the score had reached double figures. After that, Arthur Blacklock was clean bowled to become victim four; Dryden snicked off (caught again by Marshall) for number five, and Edgar Brooke was caught by Edward Cotterill to make it six for Moss.

A small recovery partnership between William McGirr and Alexander Littlejohn did to some extent stop the rot - or at least it did until the former was out caught by Edward Barnes - Moss had found his way back into the wickets. He would complete the rest of his astonishing haul without the assistance of any other fielders: Sydney Nicholls (eight) was caught-and-bowled, before William Ogier (nine) and Henry Lawson (ten) were both clean bowled.

In his first 129 deliveries in first-class cricket Albert Moss had claimed ten wickets and conceded only 28 runs. He had also strung together ten maidens on his way to recording the best bowling figures in first-class cricket history at the time, overhauling Samuel Butler's 10 for 38 taken in 24.1 four-ball overs in the 1871 Varsity Match. This record would later be equalled by Bill Howell in 1899, and beaten by Ernie Vogler in 1906, then by George Geary in 1929, by Hedley Verity in 1932 and finally by Premangsu Chatterjee in 1957. It remains the fifth-greatest innings analysis in the history of first-class history, which includes some 60,000 matches, and Moss had achieved it on his very first try. Surely he was destined for a great career?

In his second bowling effort, he again claimed the first two wickets for his team, clean bowling Littlejohn and Blacklock. However, Frederick Harman would end up starring, claiming five wickets while Moss would take only one more, ending with "only" thirteen for the match and overall figures of 46.3-16-72-13.

Later that season, he would take eight wickets for 72 in the match against Auckland, then four more wickets and score his first ever runs against a strong New South Wales team (including innings figures of three for 57 in 45 five-ball overs when he bowled unchanged from one end), and finally only one wicket against Otago.

While this was an objectively excellent return for a maiden season of first-class cricket, there was also a clear trend of diminishing returns that doesn't take a mathematician to identify. But that downward trend did not extend - yet - to the rest of Moss' life: he was overjoyed to be reunited with Mary, and they married in June 1890. Shortly after that, at a celebratory event at Lancaster Park Cricket Club, he was presented with his ten-wicket ball, mounted with an inscription relating to its provenance.

He would lose the ball, and his wife, his cricket career, and almost his own life within months. Troubled by migraines, erratic and irrational behaviour, his doctor had incorrectly diagnosed Moss with tuberculous meningitis and advised rest; a more modern diagnosis would likely be bipolar personality disorder, amplified by the frequent migraines. Regardless, Moss could not rest; he had no choice but to work, for there were bailiffs looking to reclaim money he didn't have and threatening to tear apart the home he had only just finished creating for himself. On one winter morning, Moss' sanity snapped completely.

To avoid too many lurid details, Albert Moss attacked his wife Mary with a blade, striking her more than once around the head and neck area. Despite her injuries, she managed to escape the clutches of her deranged husband, who attempted to turn the blade on himself. He more than partially succeeded in cutting his own throat, ultimately being saved by passers-by, including a certain Dr John Tweed, who had come running at the sound of Mary's screams.

Once he was fit to stand trial for attempting to kill his wife, Moss did so. The trial was not to establish whether he had tried to kill Mary: that much was self-evident and accepted by all parties. The question was whether or not he could be held criminally responsible. At the first attempt, there was a mistrial as a result of a hung jury; a new jury was summoned for a full retrial, and after only eighty minutes of deliberations they found him not guilty of attempted murder by reason of insanity, but ordered that he be imprisoned until he was deemed to be fit for release.

Despite everything, Mary continued to write affectionately to Albert while he was incarcerated. She did not intend to live with him again - to do so would, based on all available evidence, be putting herself entirely in harm's way, but she did want to offer him support as best she could. She was conflicted, and by the end of 1893 had made a decision: she moved to Marlborough, and explained that though she still cared for him, after the events that had led to his incarceration she did not believe she could ever see him again. She then wrote to the Colonial Secretary, explaining that she wanted the best for her husband - including his liberty - but also that she never wanted to see him again. Inspector of Prisons Arthur Hume came up with the solution that he would guarantee Moss his liberty, on the proviso that he agreed to leave the colony and never to return.

Moss consented, and tried to remake his life in Montevideo, Uruguay. Alone and lonely, he was thoroughly miserable: back in gainful employment on the railways, he was also able to fund an increasing dependency on alcohol to get through the days. He managed to secure a new position working on South African railways, and moved to his fourth continent in two decades. Once there, his depression did not lessen, and nor did his alcohol consumption. Both reached their depths in 1904 when he was served with divorce papers from New Zealand. The papers cited grounds of "wilful abandonment" and bore the signatures of the now ex-wife he still loved, and his own lawyer from the 1890 court case.

He saw nothing left to live for, and resolved to throw himself into the ocean.

He did not throw himself into the ocean. Instead, he threw himself into the Salvation Army. Sources suggest that he worked tirelessly from that time onwards to help recently released prisoners to turn their lives around. One source in particular reported on his deeds: War Cry, the Salvation Army's own publication. An almost certainly apocryphal story recounts how a copy of this edition of War Cry quite literally fell across Mary Moss' path while she was on a walking tour of the North Island. She picked it up and saw a name she knew very well.

Whatever the true details of how she found out about her ex-husband, shortly afterwards, Albert received a package in the mail. Inside was a mounted and engraved cricket ball, proclaiming that A.E. Moss, of Lancaster Park Cricket Club, had taken ten wickets for 28 runs for Canterbury against Wellington a quarter-century before. It was accompanied by a note: "Now I know where you are, I think you might like this souvenir of your cricket days."

Albert and Mary exchanged increasingly loving letters for three years. Mary also exchanged letters with the Salvation Army, who assured her that Albert was a changed, reformed and stable man. She made the voyage out to South Africa in 1918, and they remarried into a far happier union than their first.

In 1925, Mary's health began to decline, and the pair returned to England to see out their old age together. Mary died in 1928, and Albert lived out his final seventeen years as a widower.

As for his ball, shortly before his death he sent it back to his beloved Lancaster Park Cricket Club. The Club did not treat it with the love and care he would have hoped, and it ended up being given to Salvation Army officer Rodney Knight as an alternative to landfill. Rodney Knight died in 2005 and as of 2017, his son plans to donate it to the New Zealand Cricket Museum in Wellington.

So my first pick will be a man I've written an extensive profile on in the past:

First-class stats: 26 wickets @ 10.96 (2 5WI, best 10/28) in 4 matches

Few have heard of former Canterbury fast bowler Albert Edward Moss, and given that he played all of four first-class matches there would usually be very little reason for them to have done. Born in Coalville, Leicestershire in 1863, he made the difficult decision to emigrate as a young man to escape the spread of tuberculosis through his family. It meant leaving behind his fiancée, Mary Hall, with the aim that they would be reunited in New Zealand.

He settled in Canterbury, New Zealand; where cricket had been a recreational activity for him in England, it increasingly became a way of life as he crafted a fearsome reputation for himself as a fast bowler at club level for Lancaster Park. His numbers spoke for themselves and demanded his selection for a first-class debut against Wellington at Hagley Oval in 1889. Batting at number eleven, his debut began inauspiciously as he was out for a duck, caught by Henry Lawson to become Charles Dryden's seventh wicket in the innings.

The debutant was entrusted with the new ball, and would be running in with the full weight of his reputation thundering behind him. With only three runs on the board, he struck: Wellington captain William Salmon out, caught behind by wicketkeeper George Marshall. Moments later, the dangerous Robert Blacklock was out too, caught by Charles Garrard. Malcolm Moorhouse became Moss' third wicket and Marshall's second dismissal before the score had reached double figures. After that, Arthur Blacklock was clean bowled to become victim four; Dryden snicked off (caught again by Marshall) for number five, and Edgar Brooke was caught by Edward Cotterill to make it six for Moss.

A small recovery partnership between William McGirr and Alexander Littlejohn did to some extent stop the rot - or at least it did until the former was out caught by Edward Barnes - Moss had found his way back into the wickets. He would complete the rest of his astonishing haul without the assistance of any other fielders: Sydney Nicholls (eight) was caught-and-bowled, before William Ogier (nine) and Henry Lawson (ten) were both clean bowled.

In his first 129 deliveries in first-class cricket Albert Moss had claimed ten wickets and conceded only 28 runs. He had also strung together ten maidens on his way to recording the best bowling figures in first-class cricket history at the time, overhauling Samuel Butler's 10 for 38 taken in 24.1 four-ball overs in the 1871 Varsity Match. This record would later be equalled by Bill Howell in 1899, and beaten by Ernie Vogler in 1906, then by George Geary in 1929, by Hedley Verity in 1932 and finally by Premangsu Chatterjee in 1957. It remains the fifth-greatest innings analysis in the history of first-class history, which includes some 60,000 matches, and Moss had achieved it on his very first try. Surely he was destined for a great career?

In his second bowling effort, he again claimed the first two wickets for his team, clean bowling Littlejohn and Blacklock. However, Frederick Harman would end up starring, claiming five wickets while Moss would take only one more, ending with "only" thirteen for the match and overall figures of 46.3-16-72-13.

Later that season, he would take eight wickets for 72 in the match against Auckland, then four more wickets and score his first ever runs against a strong New South Wales team (including innings figures of three for 57 in 45 five-ball overs when he bowled unchanged from one end), and finally only one wicket against Otago.

While this was an objectively excellent return for a maiden season of first-class cricket, there was also a clear trend of diminishing returns that doesn't take a mathematician to identify. But that downward trend did not extend - yet - to the rest of Moss' life: he was overjoyed to be reunited with Mary, and they married in June 1890. Shortly after that, at a celebratory event at Lancaster Park Cricket Club, he was presented with his ten-wicket ball, mounted with an inscription relating to its provenance.

He would lose the ball, and his wife, his cricket career, and almost his own life within months. Troubled by migraines, erratic and irrational behaviour, his doctor had incorrectly diagnosed Moss with tuberculous meningitis and advised rest; a more modern diagnosis would likely be bipolar personality disorder, amplified by the frequent migraines. Regardless, Moss could not rest; he had no choice but to work, for there were bailiffs looking to reclaim money he didn't have and threatening to tear apart the home he had only just finished creating for himself. On one winter morning, Moss' sanity snapped completely.

To avoid too many lurid details, Albert Moss attacked his wife Mary with a blade, striking her more than once around the head and neck area. Despite her injuries, she managed to escape the clutches of her deranged husband, who attempted to turn the blade on himself. He more than partially succeeded in cutting his own throat, ultimately being saved by passers-by, including a certain Dr John Tweed, who had come running at the sound of Mary's screams.

Once he was fit to stand trial for attempting to kill his wife, Moss did so. The trial was not to establish whether he had tried to kill Mary: that much was self-evident and accepted by all parties. The question was whether or not he could be held criminally responsible. At the first attempt, there was a mistrial as a result of a hung jury; a new jury was summoned for a full retrial, and after only eighty minutes of deliberations they found him not guilty of attempted murder by reason of insanity, but ordered that he be imprisoned until he was deemed to be fit for release.

Despite everything, Mary continued to write affectionately to Albert while he was incarcerated. She did not intend to live with him again - to do so would, based on all available evidence, be putting herself entirely in harm's way, but she did want to offer him support as best she could. She was conflicted, and by the end of 1893 had made a decision: she moved to Marlborough, and explained that though she still cared for him, after the events that had led to his incarceration she did not believe she could ever see him again. She then wrote to the Colonial Secretary, explaining that she wanted the best for her husband - including his liberty - but also that she never wanted to see him again. Inspector of Prisons Arthur Hume came up with the solution that he would guarantee Moss his liberty, on the proviso that he agreed to leave the colony and never to return.

Moss consented, and tried to remake his life in Montevideo, Uruguay. Alone and lonely, he was thoroughly miserable: back in gainful employment on the railways, he was also able to fund an increasing dependency on alcohol to get through the days. He managed to secure a new position working on South African railways, and moved to his fourth continent in two decades. Once there, his depression did not lessen, and nor did his alcohol consumption. Both reached their depths in 1904 when he was served with divorce papers from New Zealand. The papers cited grounds of "wilful abandonment" and bore the signatures of the now ex-wife he still loved, and his own lawyer from the 1890 court case.

He saw nothing left to live for, and resolved to throw himself into the ocean.

He did not throw himself into the ocean. Instead, he threw himself into the Salvation Army. Sources suggest that he worked tirelessly from that time onwards to help recently released prisoners to turn their lives around. One source in particular reported on his deeds: War Cry, the Salvation Army's own publication. An almost certainly apocryphal story recounts how a copy of this edition of War Cry quite literally fell across Mary Moss' path while she was on a walking tour of the North Island. She picked it up and saw a name she knew very well.

Whatever the true details of how she found out about her ex-husband, shortly afterwards, Albert received a package in the mail. Inside was a mounted and engraved cricket ball, proclaiming that A.E. Moss, of Lancaster Park Cricket Club, had taken ten wickets for 28 runs for Canterbury against Wellington a quarter-century before. It was accompanied by a note: "Now I know where you are, I think you might like this souvenir of your cricket days."

Albert and Mary exchanged increasingly loving letters for three years. Mary also exchanged letters with the Salvation Army, who assured her that Albert was a changed, reformed and stable man. She made the voyage out to South Africa in 1918, and they remarried into a far happier union than their first.

In 1925, Mary's health began to decline, and the pair returned to England to see out their old age together. Mary died in 1928, and Albert lived out his final seventeen years as a widower.

As for his ball, shortly before his death he sent it back to his beloved Lancaster Park Cricket Club. The Club did not treat it with the love and care he would have hoped, and it ended up being given to Salvation Army officer Rodney Knight as an alternative to landfill. Rodney Knight died in 2005 and as of 2017, his son plans to donate it to the New Zealand Cricket Museum in Wellington.

Okay, so first of all apologies for my lateness - I didn't pick up the tag to make my pick.

No worries, you have the next pick in one test wonder as well in case you didn't get that tag either

Aislabie

Test Cricket is Best Cricket

Moderator

Ireland

PlanetCricket Award Winner

Champions League Winner

First class stats: 207 runs in his only first-class innings

Norman Callaway burst onto the Australian cricketing scene in just about the most explosive way possible. Aged only seventeen, he joined Waverley Cricket Club and immediately dominated First Grade. He also dominated his resulting New South Wales Second XI debut by flaying an imperious 129 against Victoria. By the time he made his fist-class debut shortly after his eighteenth birthday, he was already getting national attention. On a difficult pitch, Queensland had been bowled out for just 137 in a little over a session; Waddy, Andrews and Ratcliffe all quickly lost their wickets to McAndrew in reply, which meant that the teenager walked out with the total on 17 for three.

Callaway turned the game on its head: within an hour, he had reached his debut fifty. Half an hour later, he launched a straight six into the pavilion to bring up his century after just another half-hour of batting. It was the sort of batting display that just didn't occur in those days, particularly not on one's first day as a first-class cricketer. He resumed the second day unbeaten on 125, and picked up where he had left off by racing to a double hundred. He was at the time only the second man (still a boy, really) to have done so on first-class debut. The man at the other end was his captain: by this point a legend in his own right, mostly for his aggressive style of batting, Charlie Macartney played a distant second fiddle to the boy from Waverley. Queensland would lose the game by an innings and 231 runs after just eight hours and 38 minutes of play.

This all happened on the 19th and 20th of February 1915. That falls squarely into a period of history that is well-known for another reason: Callaway would enlist to fight for his country in the First World War. He was deployed to France, where he would be killed barely two years on from his remarkable innings. The ball that he faced up to with his score on 207, which he edged to the keeper, and which deflected off the keeper's gloves into the hands of what must have been the only slip fielder left for Queensland, would be the last one he ever faced in first-class cricket.

@Aislabie 's Second XI so far:

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

@ahmedleo414

My Next pick goes to Alan Jones of Wales(couldn't find a welsh flag)/

His bio from cricinfo:

"All cricket, certainly the British county scene and, above all, the Welsh game, are much the poorer for the retirement of Alan Jones. Glamorgan's major batsman for more than 20 years, he scored more runs and more centuries, made a thousand in a season more often, than any other player in the county's history, and shared in the record stand for any wicket. He was also the ideal senior pro, recalling the great holders of that office in a more idealistic day than this.

It is strange that he should have set so many records, for he was never a record-chaser. It is, though, a savage irony that his only selection for England was in the massive con trick - as cynical as any ever pulled in cricket - which called the England v The Rest of the World fixtures of 1970 `Test matches'. So, like Don Shepherd, he was never to play for England; these two Welshmen must be the finest cricketers of the post-war - or perhaps any other - period never to win a Test cap.

Alan Jones was a splendid county cricketer. Contented and conscientious as his county's senior pro, he did not aspire to power; but twice, at Glamorgan's need, he took over the captaincy in characteristically dutiful fashion. Nothing flashy or risky, of course; all according to the book, but he was unfailingly sympathetic towards the younger players, many of whom flourished more handsomely under him than at any other time. He took that post most notably in 1977, after the most violent upheaval inside the team, and throughout the membership, that Glamorgan had ever known. Then, Alan Jones did not merely compel respect, he alone seemed above any suspicion. He lifted a side afflicted with self-doubt not simply to self-respect, but to the final of the Gillette Cup. Always, though, he was happy to hand over control and return to concentrate on what he saw as his real purpose, that of making runs - Glamorgan runs, of course."

My Team so far:

1.

Alan Jones

Alan Jones

2.

3.

James Aitchison

James Aitchison

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

@Asham you have the next pick

Stats|Matches|Runs|Top Score|Batting Ave|100s/50s

First-Class|645|36,049|204*|32.89|56/194

First-Class|645|36,049|204*|32.89|56/194

"All cricket, certainly the British county scene and, above all, the Welsh game, are much the poorer for the retirement of Alan Jones. Glamorgan's major batsman for more than 20 years, he scored more runs and more centuries, made a thousand in a season more often, than any other player in the county's history, and shared in the record stand for any wicket. He was also the ideal senior pro, recalling the great holders of that office in a more idealistic day than this.

It is strange that he should have set so many records, for he was never a record-chaser. It is, though, a savage irony that his only selection for England was in the massive con trick - as cynical as any ever pulled in cricket - which called the England v The Rest of the World fixtures of 1970 `Test matches'. So, like Don Shepherd, he was never to play for England; these two Welshmen must be the finest cricketers of the post-war - or perhaps any other - period never to win a Test cap.

Alan Jones was a splendid county cricketer. Contented and conscientious as his county's senior pro, he did not aspire to power; but twice, at Glamorgan's need, he took over the captaincy in characteristically dutiful fashion. Nothing flashy or risky, of course; all according to the book, but he was unfailingly sympathetic towards the younger players, many of whom flourished more handsomely under him than at any other time. He took that post most notably in 1977, after the most violent upheaval inside the team, and throughout the membership, that Glamorgan had ever known. Then, Alan Jones did not merely compel respect, he alone seemed above any suspicion. He lifted a side afflicted with self-doubt not simply to self-respect, but to the final of the Gillette Cup. Always, though, he was happy to hand over control and return to concentrate on what he saw as his real purpose, that of making runs - Glamorgan runs, of course."

My Team so far:

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

@Asham you have the next pick

- Joined

- Jun 8, 2014

- Location

- Pune

- Online Cricket Games Owned

- Don Bradman Cricket 14 - PS3

- Don Bradman Cricket 14 - Steam PC

- Joined

- Jun 8, 2014

- Location

- Pune

- Online Cricket Games Owned

- Don Bradman Cricket 14 - PS3

- Don Bradman Cricket 14 - Steam PC

Asham's XI

1)

2)

3)

4)

5)

6)

7)

8)

9)

10)

11)

@Yash. to pick the next.

Yash.

ICC Board Member

India

Ireland

ENG....

SRH...

QG

PlanetCricket Award Winner

Melbourne Stars

X Rebels

My pick would be Padmakar Shivalkar.

The highest wicket taker ever for the most successful team in Ranji Trophy. Padmakar Shivalkar was a really potent left arm spinner, who took 589 wickets in his first class career for Bombay at an average of 19. He’ll be a great weapon in my team.

@VC the slogger

The highest wicket taker ever for the most successful team in Ranji Trophy. Padmakar Shivalkar was a really potent left arm spinner, who took 589 wickets in his first class career for Bombay at an average of 19. He’ll be a great weapon in my team.

@VC the slogger

Similar threads

- Replies

- 85

- Views

- 13K

- Replies

- 120

- Views

- 20K

Users who are viewing this thread

Total: 2 (members: 0, guests: 2)